- 4 Sections

- 6 Lessons

- 1 Day

- SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION2

- SECTION 2: AUTOMOTIVE ELECTRICAL & ELECTRONIC COMPONENTS3

- SECTION 3: WIRING DIAGRAMS1

- QUIZ1

Curriculum

Theories and laws of electricity

Introduction

Electricity is at the core of all modern automotive systems. Every function in a vehicle—from starting the engine, charging the battery, powering lights, controlling sensors, operating ECUs, to enabling communication networks—depends on a clear understanding of electrical principles.

This lesson introduces the fundamental theories and laws that govern electricity.

Electrical Materials

Conductors

Conductors are materials that allow electric current to pass through them with minimal resistance. Their atomic structure contains free electrons that move easily when voltage is applied.

Examples: Copper, aluminum, silver.

Applications in Automotive Systems: Wiring harnesses, terminals, fuses, grounding straps.

Insulators

Insulators are materials that oppose the flow of electric current. They have tightly bound electrons that do not move freely. Insulators are essential for preventing short circuits and protecting technicians from electrical hazards.

Examples: Rubber, plastic, glass, ceramic.

Applications: Wire insulation, battery cases, sensor housings.

Semiconductors

Semiconductors are materials whose conductive properties fall between conductors and insulators. By adding impurities or applying heat, their electrical characteristics can be altered.

They form the basis of modern automotive electronics.

Examples: Silicon, germanium.

Applications: Diodes, transistors, control modules, voltage regulators, sensors.

Basic Electrical Quantities

Voltage (V)

Voltage is the electrical pressure or force that pushes electrons through a conductor. It is the potential difference between two points in a circuit and is measured in volts (V).

In automotive systems, voltage is supplied by the battery and regulated by the alternator.

Current (I)

Current is the rate of flow of electrons through a conductor and is measured in amperes (A).

High current flows in components such as starter motors, while low currents are found in sensors and communication circuits.

Resistance (R)

Resistance is the opposition to current flow within a material or component. It is measured in ohms (Ω).

Every electrical device, wire, or connection has some resistance, which affects system performance. Excess resistance often causes voltage drops, overheating, and poor operation.

Ohm’s Law

Ohm’s law states that the electric current flowing through a conductor is directly proportional to the voltage across it, provided that the temperature and other physical conditions remain constant.

Ohm’s Law describes the relationship between voltage (V), current (I), and resistance (R) in an electrical circuit.

This equation forms the basis for electrical diagnostics and calculations.

From the formula, the following relationships are derived:

V=I×R

I = V/R

R= V/I

Applications in Automotive Work:

-

Calculating fuse sizes.

-

Determining current draw of components.

-

Diagnosing voltage drops.

-

Understanding sensor outputs.

1.4 Types of Electrical Current

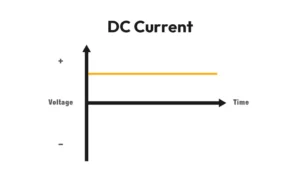

1.4.1 Direct Current (DC)

Direct current flows in one direction only.

Most automotive electrical systems primarily operate on 12V or 24V DC supplied by the vehicle battery.

Automotive Uses:

-

Starting systems

-

Lighting systems

-

ECUs and sensors

-

Relays, solenoids, actuators

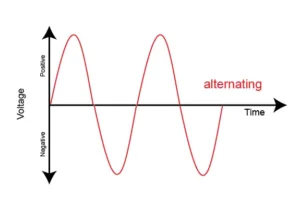

Alternating Current (AC)

Alternating current periodically reverses direction.

In vehicles, AC is produced inside the alternator and then converted to DC by a rectifier.

Automotive Uses:

-

Alternator output

-

AC-type sensors (e.g., ABS wheel speed sensors)

-

Some audio and communication circuits

Types of Electrical Circuits

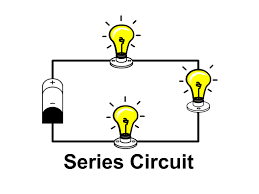

Series Circuits

In a series circuit, components are connected in a single path.

-

The same current flows through all components.

-

Total resistance is the sum of individual resistances.

-

If one component fails, the entire circuit stops working.

Example:

Some old dashboard warning lamps and certain sensor circuits.

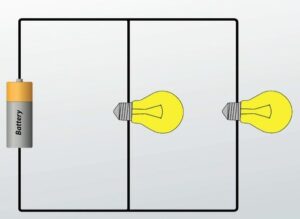

1.5.2 Parallel Circuits

In a parallel circuit, components are connected across the same voltage source.

-

Each branch receives full system voltage.

-

Current divides among the branches based on load.

-

A failure in one branch does not stop the others from working.

Example:

Headlights, interior lights, power windows, infotainment systems.